Post by maggiethecat on Jul 21, 2005 17:56:04 GMT -5

I wasn’t a regular NYPD Blue or ABC viewer so I hadn’t seen any of the promos for Blind Justice. I simply turned it on March 8th for three reasons: it was new, it was from Steven Bochco, and it wasn’t Law & Order, which I’d finally wearied of. As for Ron Eldard, I remembered him vaguely from the early days of ER, but that was about it.

The first shot hooked me . . . the close-up of Eldard’s eyes, alert, sharply focused, as he entered into the shootout at the bank. As the scene progressed -- bleached palette, jump cuts, voices slowed, fragged images edited so you felt the confusion but still knew exactly what was happening -- I realized I was holding my breath, not quite believing what I was seeing. Not quite believing that this good-looking blond guy, whoever he was -- “Terry, he’s empty, take the shot, Terry!” -- had to cross the street to wrest the gun from the hands of his cowering partner, and calmly and purposefully walk toward the gunman and fire the shot that tore out his jugular, and then -- immediately -- the horrific shock of the bullet tearing across his temple, his head jerking back . . . and the bookend, the second close-up of Eldard’s eyes, blank, unseeing, his face pallid and damp with sweat.

I remember thinking -- and I still do -- that it was just about the most compelling two minutes I’d ever seen on film. And I couldn’t believe I was seeing it on network television.

Now, from a distance, one of the reasons I find the opening so valuable is not only because it set up the premise of the show -- and brilliantly -- but because it is the best evidence we have of the kind of cop Jim Dunbar was before he was blinded. And he was about as good as it gets: smart, supremely confident, intuitive, quick to act, and brave as hell.

In a very real sense, the creators of Blind Justice were following the most ancient and basic precepts of Greek tragedy: the hero must fall from a great height . . . and then climb back up.

Images, coming thick and fast. Making coffee, shaving, the ordinary details of an un-ordinary life. Jim packing for work, putting his laptop and cane in his bag, then reaching into the desk drawer for a detective’s shield and a gun. (A gun? How is this going to play out?) Christie, keeping the tension out of her voice but not off her face or her twisting hands as he walks out the door.

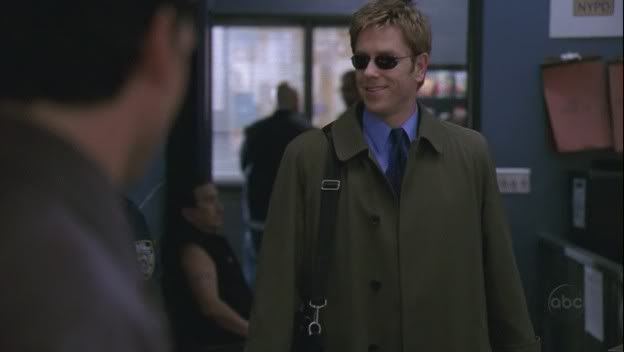

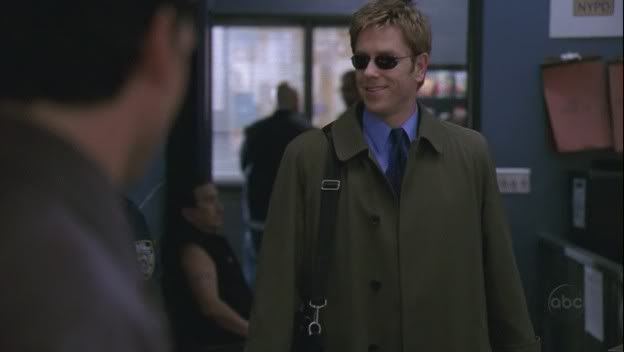

The subway, the street, people staring, the reporters. Have we even hit the ten minute mark yet? And then the squad room. Does this guy make an entrance or what? Tall, good-looking and well dressed, the shades, the dog, the pained half-smile.

And the silence that falls. “Jim Dunbar for Lieutenant Fisk.” Fisk waving him off through the window. “He’s on the phone.” “I’m assigned here.” Marty answering, sourly, “We know.” And we’re off and running.

It was all there, the characters set up swiftly and skillfully: Jim, the tragic hero on a journey of redemption, Christie, the injured but faithful wife, Karen, the loyal partner/friend, Marty, the hotheaded rival, Tom, the ultimate nice guy, and Fisk, the eye of the hurricane. Characters so strongly established that the writers were then afforded the luxury of nuance, the small character “reveal,” the telling moments we all came to wait for.

Although others have said they like the way Dunbar’s sense of humor was revealed as the show progressed, I think it was there from the beginning. Granted, it was the kind of humor you use to diffuse tension when you’re the Odd Man Out, but it was one aspect (of many) that made this character so likeable. “Anyone allergic to dogs?” “So who’m I riding with, being as how the dog can’t drive?” Think about that last line for a minute. It follows directly on the heels of the interview with Fisk: what are you going to do (i.e. contribute) at a crime scene, the gun waiver, and the fact, baldly stated, that while Dunbar was respected, that was yesterday’s news and no one wanted to work with him. The look on Dunbar’s face as he struggles to absorb the blow, yet respond positively, is a heartbreaker. (I vote for this shot as one of the finest close-ups of the series, second only to the scene with Galloway in "Marlon's Brando.")

The day Jim Dunbar has been working toward for a year is turning to ashes in his mouth, but he’s still cool enough to joke about his guide dog. When life is at its bleakest, humor can be the best weapon in your arsenal. Sometimes it’s the only weapon.

Which he will need, as it's evident that Fisk is not about to put him -- or his other detectives -- in harm's way. The Chief of Ds has handed Fisk this high profile media superstar, this brave but blinded tec, this accident waiting to happen . . . and so, while he will use Dunbar, it will not be in a major way. Want to work cases, Jim? Fine. Forget the Tongue Collector pross homicides. Here's a stolen car, complete with cremated dog ashes. Have a kited check from a Chinatown restaurant, worth a whopping twelve dollars. Sorry, Karen, he's your partner now but because he's the NYPD's one and only "blind dude," you're going to be working cases of little or no consequence.

And Karen is furious, especially when Jim attempts to persuade her that he's no longer the ladies man who romanced her friend Anne. "I've done a lot of growing up since then," he reassures her. "Good for you," she answers, her voice dripping acid. "Meanwhile, there's a guy cuttin' out girls' tongues and I'm all of a sudden workin' a stolen car."

She's not about to cut Dunbar any sort of slack. Balls of steel at the bank don't cut any more ice with her than they do with the skeptical and confrontational ("Tell me that gun on your hip is plastic . . . ") Marty Russo. She's been pulled off a major case for "punk ass" reasons, and reason number one is James Dunbar, who can't even follow the The Boss into his office without falling all over himself.

But she's working that stolen car with a ten-year Gold Shield man who grew up in Red Hook, who fought in the Gulf War, and who worked anti-crime with a precinct that took more guns off the street than any five combined. His instincts are as sharply honed as ever, and he smells cordite in the car, the lingering effluvia from a gun having been fired recently. "This is a crime scene," he says firmly, the old confidence returned.

And, again, we're off and running.

There, too, in The Pilot -- along with the crisp, character-specific writing and the corkscrew plotting -- was Ron Eldard’s fearless and charismatic performance. He didn’t have to settle into the character. He got it right, immediately, inhabiting the altered reality of sightlessness down to the tiniest detail. I’m a fierce critic when it comes to actors “playing disabled,” as it’s more often than not an excuse for overacting -- but did Eldard ever hit one false note? Did anyone ever catch him “acting”? Can anyone think of another lead actor last season who did such sensitive, strong, and utterly persuasive work?

But I digress. (Who, me?) So many moments. Jim’s homecoming that first night, slumped against the fridge, tension and strain evident, only straightening when he hears Christie’s voice. She’s waiting, dinner on the stove, eager to hear how his first day went, and it all deteriorates in a heartbeat. Of course he’s covering, of course she knows it, and so we’re not surprised when she makes that bitter crack about “business as usual.” Nor are we surprised at his reaction. “This is incredible. You’re going to do this now? You’re going to do this today?”

As sharply played as that scene is -- and as much as it tells us about the state of their marriage -- what resonates is the way it ends, Jim sitting and flipping a ball against the living room wall. The paint is pitted, gone. You just know how much time he’s spent flipping that damned ball and brooding, and, as flawed and prickly as he is, you ache for him.

It's been the day from hell for Jim Dunbar. As he tries to tell his icily unforgiving wife, "I've been dealing with people doubting me all day." Doubt, suspicion, condescension, outright scorn -- and Terry Jansen, lying in wait like a psychological landmine.

Good old Terry. That prince of a guy whose moment of cowardice led to Jim's being blinded. Good Old Terry, who is still -- after a year of Jim ducking his calls -- looking for the forgiveness he cannot find in himself and probably doesn't deserve. Good Old Terry, who is still hoping against all hope that Jim will tell him his actions were righteous, when they so clearly were anything but. "Stop it," Jim cuts him off harshly. "We both know what happened that day. Don't you make it worse by trying to pretend differently."

So many moments, small and finely crafted. When Jim and Karen go to interview Lynn Bodner's roommate, Jim starts to take out his cane.

Karen stops him and places his hand on her arm. "You don't mind?" he asks in a moment of unexpected vulnerability. Was she being a natural, or was it because, as part of maintaining an official police presence, Jim would look less blind at her elbow than he would tapping his way along the sidewalk? Would Karen look less like she’d been saddled -- as a woman and as the junior member of the squad -- with a "damaged" partner? Perhaps a little of both. But however fleeting the moment may be, it is the beginning of trust and acceptance.

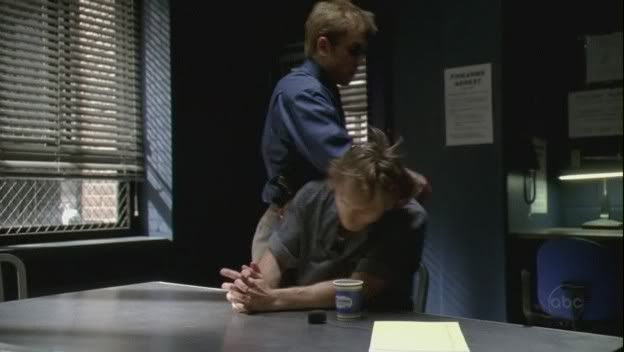

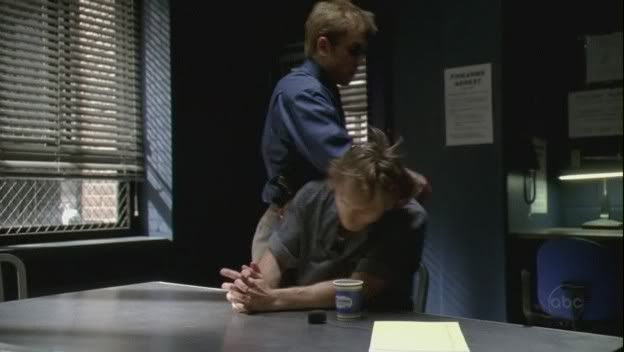

And then the scene where Jim pulls his gun on Randy Lyman. Controversial, yes, but can we stop and remember that this is fiction? The writers and actors made it work. What I take away from that scene is the contrast between the steelly resolve when Dunbar finally positions himself, knowing he’s aimed directly at Randy . . .

. . . and after, trying to pull himself together, flexing his shaking hands. So well done, so beautifully played.

When Jim finally gets his chance at an interrogation, it's masterful. Here, in short, is the Old Dunbar, the kick-ass Dunbar that was. The casual and practiced manner in which he "accidentally" clips Randy with his elbow -- how many times, and in how many ways, did he use this move in the good old, bad old days?

The evidence bag of hairs, supposedly Lyman's and taken from Lynn Bodner's body, in reality Jim's, a slick and savvy ploy no one -- not the viewer, not Fisk, and certainly not Russo and Sellway -- sees coming.

The lightening flashes of that quick, black-as-the-pit Dunbar humor. "Want us to publish a manifesto in the newspaper?" he sarcastically asks the vicious serial killer, fearlessly leaning into his face. "Want us to get your Mommy on the phone?" He will take his chances where he can, using this interrogation to confront The Boys Club directly through the two-way mirror with his “No one wants me here as a detective so I have to try a little harder” speech. And again, after, leaning against the wall, gratified that he’s been able to do what he knows he’s good at, but spent, utterly spent.

I rate the ending of the Pilot as sheer perfection, with Jim and Karen on the street, finally talking honestly and openly. It’s going to take time but they’re going to be all right, these two. He understands, because he's had a year to imagine his future, that no one in their right mind would want to partner a "guy who couldn't see." All he's asking for -- all he's wanted in his long and acrimonious fight against the department -- is a chance.

“What do you look like?" he finally asks her. “You’re such a great detective, you tell me . . . and don't overshoot the weight if you know what's good for you," Karen replies lightly. A cute and slightly flirtatious remark, rendered "safe" by his blindness. He's figured out a lot in their intense few days together: he knows the length of her hair from the way it brushes against her shoulders, he knows that she's alone or her man would be calling constantly, he knows that she's pretty because the guys in the squad keep coming up to her all . . . day . . . long. But he doesn't know the color of her eyes, and, somehow, that's important.

"Don't put your moves on me," she says, again leaping to the defensive. "That's not what I'm doing," he says, disappointed. "I just wanted to know what you look like." He and Hank walk away, through a flock of pigeons that rise to the sky like scraps of torn paper . . .

. . . and she stops him with “They're brown.” Her eyes are brown. “Okay,” he says with a quick, wistful smile. “Now I know.”

And he walks on.

Favorite episode? Maybe, when all is said and done, the Pilot.

The first shot hooked me . . . the close-up of Eldard’s eyes, alert, sharply focused, as he entered into the shootout at the bank. As the scene progressed -- bleached palette, jump cuts, voices slowed, fragged images edited so you felt the confusion but still knew exactly what was happening -- I realized I was holding my breath, not quite believing what I was seeing. Not quite believing that this good-looking blond guy, whoever he was -- “Terry, he’s empty, take the shot, Terry!” -- had to cross the street to wrest the gun from the hands of his cowering partner, and calmly and purposefully walk toward the gunman and fire the shot that tore out his jugular, and then -- immediately -- the horrific shock of the bullet tearing across his temple, his head jerking back . . . and the bookend, the second close-up of Eldard’s eyes, blank, unseeing, his face pallid and damp with sweat.

I remember thinking -- and I still do -- that it was just about the most compelling two minutes I’d ever seen on film. And I couldn’t believe I was seeing it on network television.

Now, from a distance, one of the reasons I find the opening so valuable is not only because it set up the premise of the show -- and brilliantly -- but because it is the best evidence we have of the kind of cop Jim Dunbar was before he was blinded. And he was about as good as it gets: smart, supremely confident, intuitive, quick to act, and brave as hell.

In a very real sense, the creators of Blind Justice were following the most ancient and basic precepts of Greek tragedy: the hero must fall from a great height . . . and then climb back up.

Images, coming thick and fast. Making coffee, shaving, the ordinary details of an un-ordinary life. Jim packing for work, putting his laptop and cane in his bag, then reaching into the desk drawer for a detective’s shield and a gun. (A gun? How is this going to play out?) Christie, keeping the tension out of her voice but not off her face or her twisting hands as he walks out the door.

The subway, the street, people staring, the reporters. Have we even hit the ten minute mark yet? And then the squad room. Does this guy make an entrance or what? Tall, good-looking and well dressed, the shades, the dog, the pained half-smile.

And the silence that falls. “Jim Dunbar for Lieutenant Fisk.” Fisk waving him off through the window. “He’s on the phone.” “I’m assigned here.” Marty answering, sourly, “We know.” And we’re off and running.

It was all there, the characters set up swiftly and skillfully: Jim, the tragic hero on a journey of redemption, Christie, the injured but faithful wife, Karen, the loyal partner/friend, Marty, the hotheaded rival, Tom, the ultimate nice guy, and Fisk, the eye of the hurricane. Characters so strongly established that the writers were then afforded the luxury of nuance, the small character “reveal,” the telling moments we all came to wait for.

Although others have said they like the way Dunbar’s sense of humor was revealed as the show progressed, I think it was there from the beginning. Granted, it was the kind of humor you use to diffuse tension when you’re the Odd Man Out, but it was one aspect (of many) that made this character so likeable. “Anyone allergic to dogs?” “So who’m I riding with, being as how the dog can’t drive?” Think about that last line for a minute. It follows directly on the heels of the interview with Fisk: what are you going to do (i.e. contribute) at a crime scene, the gun waiver, and the fact, baldly stated, that while Dunbar was respected, that was yesterday’s news and no one wanted to work with him. The look on Dunbar’s face as he struggles to absorb the blow, yet respond positively, is a heartbreaker. (I vote for this shot as one of the finest close-ups of the series, second only to the scene with Galloway in "Marlon's Brando.")

The day Jim Dunbar has been working toward for a year is turning to ashes in his mouth, but he’s still cool enough to joke about his guide dog. When life is at its bleakest, humor can be the best weapon in your arsenal. Sometimes it’s the only weapon.

Which he will need, as it's evident that Fisk is not about to put him -- or his other detectives -- in harm's way. The Chief of Ds has handed Fisk this high profile media superstar, this brave but blinded tec, this accident waiting to happen . . . and so, while he will use Dunbar, it will not be in a major way. Want to work cases, Jim? Fine. Forget the Tongue Collector pross homicides. Here's a stolen car, complete with cremated dog ashes. Have a kited check from a Chinatown restaurant, worth a whopping twelve dollars. Sorry, Karen, he's your partner now but because he's the NYPD's one and only "blind dude," you're going to be working cases of little or no consequence.

And Karen is furious, especially when Jim attempts to persuade her that he's no longer the ladies man who romanced her friend Anne. "I've done a lot of growing up since then," he reassures her. "Good for you," she answers, her voice dripping acid. "Meanwhile, there's a guy cuttin' out girls' tongues and I'm all of a sudden workin' a stolen car."

She's not about to cut Dunbar any sort of slack. Balls of steel at the bank don't cut any more ice with her than they do with the skeptical and confrontational ("Tell me that gun on your hip is plastic . . . ") Marty Russo. She's been pulled off a major case for "punk ass" reasons, and reason number one is James Dunbar, who can't even follow the The Boss into his office without falling all over himself.

But she's working that stolen car with a ten-year Gold Shield man who grew up in Red Hook, who fought in the Gulf War, and who worked anti-crime with a precinct that took more guns off the street than any five combined. His instincts are as sharply honed as ever, and he smells cordite in the car, the lingering effluvia from a gun having been fired recently. "This is a crime scene," he says firmly, the old confidence returned.

And, again, we're off and running.

There, too, in The Pilot -- along with the crisp, character-specific writing and the corkscrew plotting -- was Ron Eldard’s fearless and charismatic performance. He didn’t have to settle into the character. He got it right, immediately, inhabiting the altered reality of sightlessness down to the tiniest detail. I’m a fierce critic when it comes to actors “playing disabled,” as it’s more often than not an excuse for overacting -- but did Eldard ever hit one false note? Did anyone ever catch him “acting”? Can anyone think of another lead actor last season who did such sensitive, strong, and utterly persuasive work?

But I digress. (Who, me?) So many moments. Jim’s homecoming that first night, slumped against the fridge, tension and strain evident, only straightening when he hears Christie’s voice. She’s waiting, dinner on the stove, eager to hear how his first day went, and it all deteriorates in a heartbeat. Of course he’s covering, of course she knows it, and so we’re not surprised when she makes that bitter crack about “business as usual.” Nor are we surprised at his reaction. “This is incredible. You’re going to do this now? You’re going to do this today?”

As sharply played as that scene is -- and as much as it tells us about the state of their marriage -- what resonates is the way it ends, Jim sitting and flipping a ball against the living room wall. The paint is pitted, gone. You just know how much time he’s spent flipping that damned ball and brooding, and, as flawed and prickly as he is, you ache for him.

It's been the day from hell for Jim Dunbar. As he tries to tell his icily unforgiving wife, "I've been dealing with people doubting me all day." Doubt, suspicion, condescension, outright scorn -- and Terry Jansen, lying in wait like a psychological landmine.

Good old Terry. That prince of a guy whose moment of cowardice led to Jim's being blinded. Good Old Terry, who is still -- after a year of Jim ducking his calls -- looking for the forgiveness he cannot find in himself and probably doesn't deserve. Good Old Terry, who is still hoping against all hope that Jim will tell him his actions were righteous, when they so clearly were anything but. "Stop it," Jim cuts him off harshly. "We both know what happened that day. Don't you make it worse by trying to pretend differently."

So many moments, small and finely crafted. When Jim and Karen go to interview Lynn Bodner's roommate, Jim starts to take out his cane.

Karen stops him and places his hand on her arm. "You don't mind?" he asks in a moment of unexpected vulnerability. Was she being a natural, or was it because, as part of maintaining an official police presence, Jim would look less blind at her elbow than he would tapping his way along the sidewalk? Would Karen look less like she’d been saddled -- as a woman and as the junior member of the squad -- with a "damaged" partner? Perhaps a little of both. But however fleeting the moment may be, it is the beginning of trust and acceptance.

And then the scene where Jim pulls his gun on Randy Lyman. Controversial, yes, but can we stop and remember that this is fiction? The writers and actors made it work. What I take away from that scene is the contrast between the steelly resolve when Dunbar finally positions himself, knowing he’s aimed directly at Randy . . .

. . . and after, trying to pull himself together, flexing his shaking hands. So well done, so beautifully played.

When Jim finally gets his chance at an interrogation, it's masterful. Here, in short, is the Old Dunbar, the kick-ass Dunbar that was. The casual and practiced manner in which he "accidentally" clips Randy with his elbow -- how many times, and in how many ways, did he use this move in the good old, bad old days?

The evidence bag of hairs, supposedly Lyman's and taken from Lynn Bodner's body, in reality Jim's, a slick and savvy ploy no one -- not the viewer, not Fisk, and certainly not Russo and Sellway -- sees coming.

The lightening flashes of that quick, black-as-the-pit Dunbar humor. "Want us to publish a manifesto in the newspaper?" he sarcastically asks the vicious serial killer, fearlessly leaning into his face. "Want us to get your Mommy on the phone?" He will take his chances where he can, using this interrogation to confront The Boys Club directly through the two-way mirror with his “No one wants me here as a detective so I have to try a little harder” speech. And again, after, leaning against the wall, gratified that he’s been able to do what he knows he’s good at, but spent, utterly spent.

I rate the ending of the Pilot as sheer perfection, with Jim and Karen on the street, finally talking honestly and openly. It’s going to take time but they’re going to be all right, these two. He understands, because he's had a year to imagine his future, that no one in their right mind would want to partner a "guy who couldn't see." All he's asking for -- all he's wanted in his long and acrimonious fight against the department -- is a chance.

“What do you look like?" he finally asks her. “You’re such a great detective, you tell me . . . and don't overshoot the weight if you know what's good for you," Karen replies lightly. A cute and slightly flirtatious remark, rendered "safe" by his blindness. He's figured out a lot in their intense few days together: he knows the length of her hair from the way it brushes against her shoulders, he knows that she's alone or her man would be calling constantly, he knows that she's pretty because the guys in the squad keep coming up to her all . . . day . . . long. But he doesn't know the color of her eyes, and, somehow, that's important.

"Don't put your moves on me," she says, again leaping to the defensive. "That's not what I'm doing," he says, disappointed. "I just wanted to know what you look like." He and Hank walk away, through a flock of pigeons that rise to the sky like scraps of torn paper . . .

. . . and she stops him with “They're brown.” Her eyes are brown. “Okay,” he says with a quick, wistful smile. “Now I know.”

And he walks on.

Favorite episode? Maybe, when all is said and done, the Pilot.

They make the posts so much better!

They make the posts so much better!